During our November road trip from Asheville to Austin, we stopped in Montgomery, Alabama, to visit the remarkable National Memorial for Peace and Justice. The open-air pavilion dedicated to 4,000+ Black victims of lynching wraps a hilltop overlooking downtown Montgomery, near where Jefferson Davis, president of the Confederacy, is still honored with a statue in front of the state capitol building. I’d read about the memorial, which opened in 2018, in the New York Times, which declared, “There is nothing like it in the country. Which is the point.”

The memorial is somber and incredibly powerful, and it reminded me in its monolithic, inscribed simplicity of the Vietnam Veterans Memorial in Washington, D.C. It demands of visitors a clear-eyed reckoning with an era of vigilante racial terror in our country during the period from 1877 to 1950.

Those seven decades when lynchings terrorized Black Americans are only a portion of the terrible legacy of slavery in the U.S., which we its citizens continue to grapple with today. It’s fitting that the memorial is located in Montgomery, where the Confederacy inaugurated its president and where, 100 years later, Martin Luther King, Jr. led the march for voting rights from Selma.

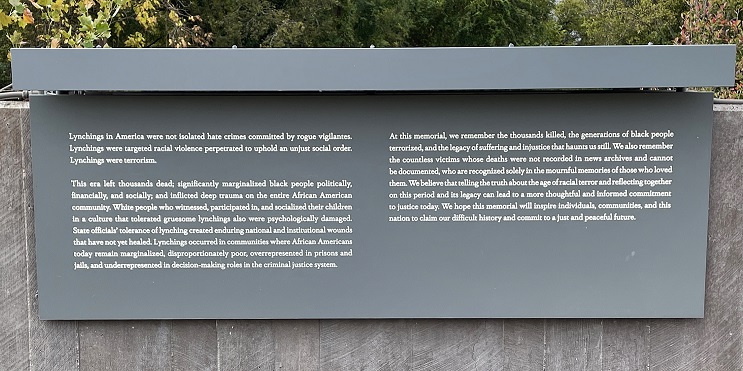

Why build — or visit — a memorial that reminds us of evils that humans visit upon other humans? The Equal Justice Initiative — the Montgomery-based nonprofit organization that created the memorial — explains:

“EJI believes that publicly confronting the truth about our history is the first step towards recovery and reconciliation.

A history of racial injustice must be acknowledged, and mass atrocities and abuse must be recognized and remembered, before a society can recover from mass violence. Public commemoration plays a significant role in prompting community-wide reconciliation.

The National Memorial for Peace and Justice provides a sacred space for truth-telling and reflection about racial terrorism and its legacy.”

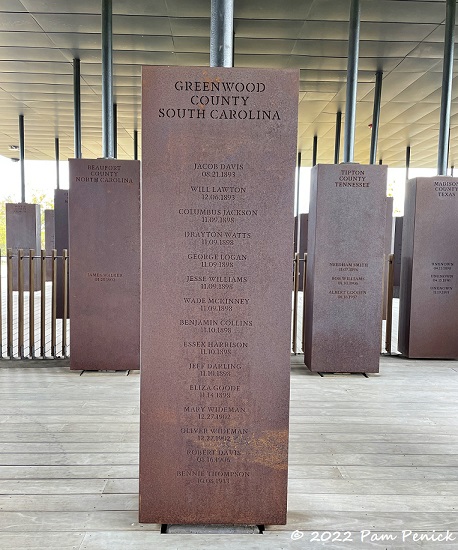

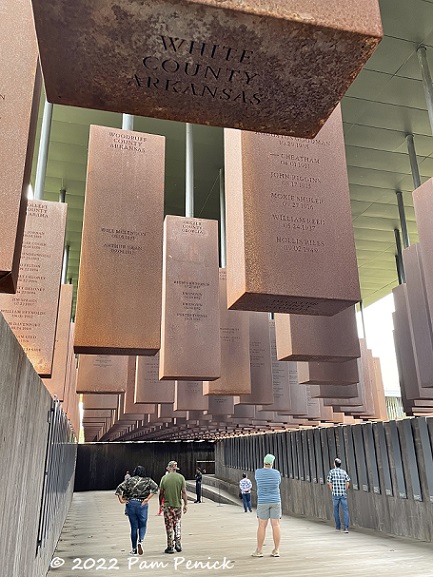

The memorial structure consists of a square, open-air pavilion displaying 800 Corten steel slabs — one for each U.S. county where a documented lynching took place. Inscribed on each slab, under the county and state, are the names of murdered individuals and the dates of their deaths.

Just that. Names of men, women, and children. When they were killed. And where. The upright monuments resemble cemetery headstones as you enter the memorial. I’d bet that most visitors search out the counties where they’ve lived, as I did. I grew up in Greenwood, South Carolina, and was aghast to find its county’s slab engraved top to bottom with 15 names. Two women are memorialized, as are nine people lynched during a week-long vigilante massacre in November 1898 known as the Phoenix Election Riot.

As you walk among the monuments, the floor begins to slope downward. The steel slabs remain at the original level, suspended from metal poles. The effect is that the 6-foot-tall blocks look as if they are being hoisted. Lights set in boxes on the floor illuminate the slabs after dark.

As you descend into the memorial, the monuments hang overhead. To read the names, you’re forced to look up, in an echo of the postures of the bloodthirsty perpetrators, gawking witnesses, and traumatized bereaved.

The monuments line up like an orderly forest. Their inscribed names provide a sense of the magnitude of this harrowing history. On the walls, plaques tonelessly detail some of the alleged offenses for which Black victims were killed, including “suing the white man who killed his cow” and “using inappropriate language with a white woman.” One person was lynched by association, “by a mob searching for her brother.”

Facing up to our nation’s history of lynching is emotionally difficult. But the victims — silenced without due process, justice, or sometimes even the dignity of being named in public records — deserve remembrance.

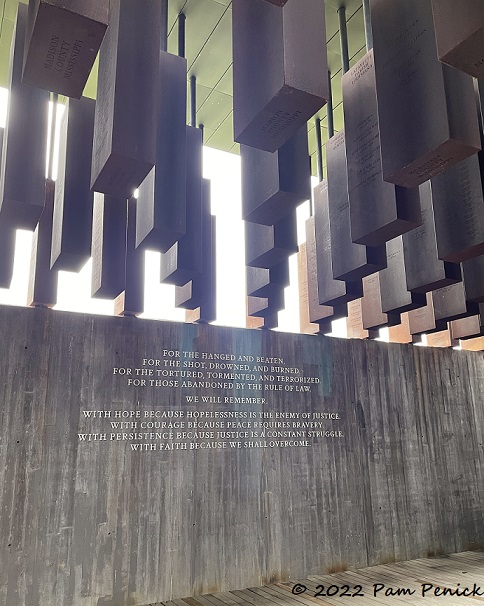

A dedication on one wall reads:

For the hanged and beaten.

For the shot, drowned, and burned.

For the tortured, tormented, and terrorized.

For those abandoned by the rule of law.

We will remember.

With hope because hopelessness is the enemy of justice.

With courage because peace requires bravery.

With persistence because justice is a constant struggle.

With faith because we shall overcome.

In the center, in what’s called Memorial Square — an evocation of the public squares and courthouse lawns where justice was subverted and victims terrorized — you’re surrounded by the names on their monuments.

Outside the memorial building, lined up like coffins, lie duplicates of the engraved monuments, one for each county. The Equal Justice Initiative hopes that representatives from each county will claim their marker, bringing it home to memorialize local lynching victims and “foster meaningful dialogue about race and justice.”

Visitors can judge for themselves, based on which monuments have been claimed and which have not, whether progress in acknowledging racial terror is being made.

The 6-acre memorial site also displays several works of sculpture, including Raise Up by Hank Willis Thomas. Ten bronze figures immobilized in concrete, with arms raised, are lined up as if facing gun barrels and shouts of “Hands where I can see them!”

A couple of blocks away, The Legacy Museum — an accompanying project to the memorial — offers another challenging but eye-opening experience for visitors. Visitors are not allowed to take photos inside the museum, but it’s a richly visual and sensory journey through the exhibits.

A Maya Angelou quote on the museum’s exterior offers a gleam of hope for us all: “History, despite its wrenching pain, cannot be unlived, but if faced with courage, need not be lived again.” If you have an opportunity to visit Montgomery, be courageous and go see it.

My final posts about our Southeast road trip are up next: A 2-part visit to Shangri La Botanical Gardens and Nature Center in Orange, Texas. For a look back at our visit to Chimney Rock near Asheville, click here.

I welcome your comments. Please scroll to the end of this post to leave one. If you’re reading in an email, click here to visit Digging and find the comment box at the end of each post. And hey, did someone forward this email to you, and you want to subscribe? Click here to get Digging delivered directly to your inbox!

All material © 2022 by Pam Penick for Digging. Unauthorized reproduction prohibited.

The post Facing history with courage at the National Memorial for Peace and Justice appeared first on Digging.